The Founder Factor: Personality and Startup Success

New research published in Nature’s Scientific Reports shows that a founder’s personality is a key predictor of start-up success—more influential than industry or company age. Researchers from UNSW Sydney, UTS, the University of Oxford, and the University of Melbourne analysed over 21,000 founder-led companies using machine learning to infer Big Five personality traits from Twitter activity. Traits like openness to adventure, confidence, and high energy were strongly linked to successful ventures.

The study identified six distinct founder types—Fighters, Operators, Accomplishers, Leaders, Engineers, and Developers. Start-ups with diverse combinations of these personalities, especially in teams of three or more, were far more likely to succeed. This insight led to the Ensemble Theory of Success, highlighting that complementary personality traits in founding teams significantly boost start-up outcomes.

These findings have wide applications beyond start-ups, emphasizing the value of personality diversity in all team-based industries. They also suggest that up to 8% of people globally may have untapped potential as successful founders, offering valuable insights for entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers.

From Elon Musk’s supreme confidence to Jeff Bezos’ ability to make smart decisions under pressure, some of the most successful entrepreneurs are known for their distinctive personalities. But these traits aren’t just interesting side notes to these founders’ stories: confidence and calmness, along with other qualities such as a love of adventure, can have a big impact on startup success.

A startup is typically counted as a “success” if it’s acquired by another company or goes public (that is, its shares become available to trade on a stock exchange). And common investor wisdom attributes this to either supply side (novel products) or demand side (market interest or “hot sectors”) factors.

Of course, many other elements are associated with startup success. There’s a “Goldilocks age” for startups, for example, with those younger than seven years old less likely to be successful because they haven’t had enough time to develop. Startups based in hot spots like San Francisco, Berlin or London are also more likely to succeed due to better access to finance and talent.

Nature’s Scientific Reports has published our new research that shows all these elements are important, it reveals that the personalities of founders are actually the most influential factor in startup success.

Our multidisciplinary team from the University of New South Wales, the University of Oxford, University of Technology Sydney and the University of Melbourne embarked on a two-year mission to unravel the mysteries behind startup success. We tapped into detailed data on more than 21,000 global startups to discern patterns that might predict a venture’s triumph or downfall.

Using AI algorithms, we applied the “five-factor” model – a psychology theory that divides personality into five main groups – to analyse startup founders worldwide. After comparing data on thousands of successful founders to information about employees, we discovered that entrepreneurs exhibit very different combinations of personality traits to everyone else.

Entrepreneurs tend to have a penchant for variety and novelty. They often have a desire to be the centre of attention and an inherent exuberance. While these traits might sound generic, in the business world they translate into risk-taking, networking and relentless energy – critical ingredients for startup success.

Based on our findings, we have identified six distinct founder personality types: leader, accomplisher, operator, developer, fighter and engineer. Each type has its own combination of subtle personality traits, for example, operators value orderliness and fighters are emotionally sensitive.

Many of these personality types are thriving in the real-life startup world. Take, for instance, Bill Gates, co-founder of Microsoft. He left Harvard to chase what was then a risky dream. This epitomises “openness to adventure”, which we found was a characteristic of the “leader” personality type.

This theme of defying the odds coupled with seemingly limitless energy resonates with many founder stories.

Melanie Perkins, a co-founder of $26 billion graphic design software company Canva, faced over 100 rejections from investors before securing the venture capital funding needed to build the platform. She has described herself as “determined, stubborn and adventurous” – also traits of the “leader” founder type.

Jeff Bezos is a well-known “acccomplisher”. He left his secure position at a New York hedge fund to found Amazon from Seattle. This wasn’t an impulsive move, it was a strategic choice. Bezos saw Seattle as the best place for a national distribution hub because it would benefit from Washington state’s specific tax laws. Such meticulous planning and long-term vision has characterised some of Amazon’s other achievements, including the development of Amazon Web Services, a global cloud computing leader.

And, of course, no discussion of start-up personalities would be complete without Tesla and Space-X founder Elon Musk. This “engineer’s” many business interests are driven by boundless imagination, as well as intellect. You can see this in SpaceX’s audacious goal to colonise Mars and Tesla’s futuristic Cybertruck design, as well as Musk’s underground transportation system Hyperloop.

Our model also indicated that startups with a diverse blend of these founder personality types are 8 to 10 times more likely to be successful.

Canva’s three co-founders are a great example of this. Ex-Googler Cameron Adams’s technical intellect and imagination has combined with Cliff Obrecht’s assertive dealmaking and Perkins’ energy, trustworthiness and adventurousness to create a tech juggernaut.

Even if you’re not gearing up to launch or invest in the next big startup, personality offers a fascinating lens through which to view the start-up world and its most talked-about figures. And these findings are likely to hold in other settings too: team performance is shaped by the right combination of different personalities.

Behind every successful startup, there’s more than just a groundbreaking product or a burgeoning market, there’s a dynamic founder – or founders – with a personality that’s the secret to startup success.

From The Conversation read the original article here.

How technology is influencing economic diversity

by the World Economic Forum

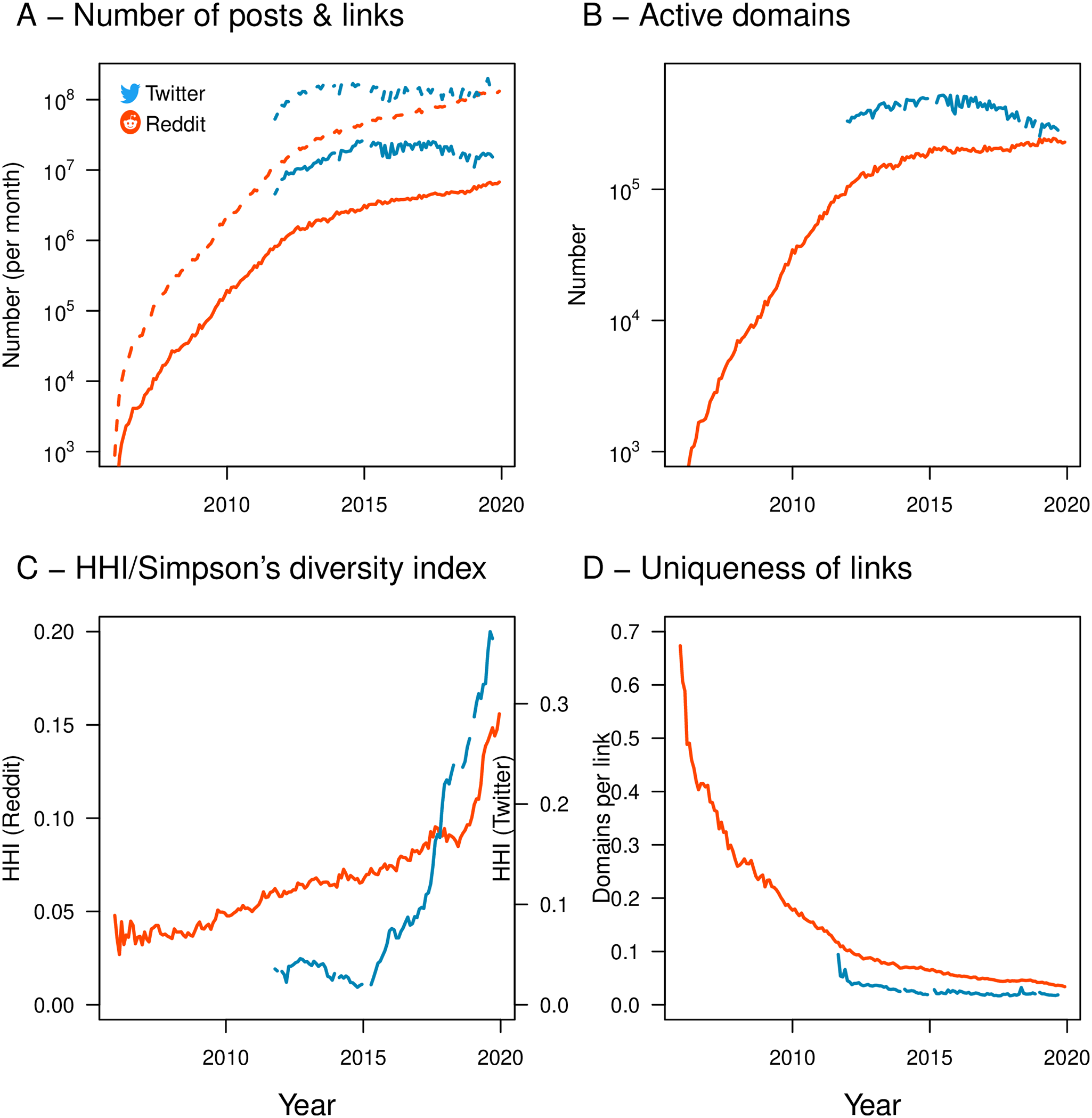

• Researchers have conducted a multi-year project analysing global trends in online diversity and dominance.

• It analysed more than six billion user comments from Reddit, as well as 11.8 billion posts from Twitter.

• The results show a dramatic consolidation of attention towards a shrinking (but increasingly dominant) group of online organisations.

The online world is continuously expanding — always aggregating more services, more users and more activity. Last year, the number of websites registered on the “.com” domain surpassed 150,000,000.

However, more than a quarter of a century since its first commercial use, the growth of the online world is now slowing down in some key categories.

We conducted a multi-year research project analysing global trends in online diversity and dominance. Our research, published today in Public Library of Science, is the first to reveal some long-term trends in how businesses compete in the age of the web.

We saw a dramatic consolidation of attention towards a shrinking (but increasingly dominant) group of online organisations. So, while there is still growth in the functions, features and applications offered on the web, the number of entities providing these functions is shrinking.

Web diversity nosedives

We analysed more than six billion user comments from the social media website Reddit dating back to 2006, as well as 11.8 billion Twitter posts from as far back as 2011. In total, our research used a massive 5.6Tb trove of data from more than a decade of global activity.

This dataset was more than four times the size of the original data from the Hubble Space Telescope, which helped Brian Schmidt and colleagues do their Nobel-prize winning work in 1998 to prove the universe’s expansion is accelerating.

With the Reddit posts, we analysed all the links to other sites and online services — more than one billion in total — to understand the dynamics of link growth, dominance and diversity through the decade.

We used a measure of link “uniqueness”. On this scale, 1 represents maximum diversity (all links have their own domain) and 0 is minimum diversity (all links are on one domain, such as “youtube.com”).

A decade ago, there was a much greater variety of domains within links posted by users of Reddit, with more than 20 different domains for every 100 random links users posted. Now there are only about five different domains for every 100 links posted.

In fact, between 60—70% of all attention on key social media platforms is focused towards just ten popular domains.

Beyond social media platforms, we also studied linkage patterns across the web, looking at almost 20 billion links over three years. These results reinforced the “rich are getting richer” online.

The authority, influence and visibility of the top 1,000 global websites (as measured by network centrality or PageRank) is growing every month, at the expense of all other sites.

App diversity is on the rise

The web started as a source of innovation, new ideas and inspiration — a technology that opened up the playing field. It’s now also becoming a medium that actually stifles competition and promotes monopolies and the dominance of a few players.

Our findings resolve a long-running paradox about the nature of the web: does it help grow businesses, jobs and investment? Or does it make it harder to get ahead by letting anyone and everyone join the game? The answer, it turns out, is it does both.

While the diversity of sources is in decline, there is a countervailing force of continually increasing functionality with new services, products and applications — such as music streaming services (Spotify), file sharing programs (Dropbox) and messaging platforms (Messenger, Whatsapp and Snapchat).

Another major finding was the dramatic increase in the “infant mortality” rate of websites — with the big kids on the block guarding their turf more staunchly than ever.

We examined new domains that were continually referenced or linked-to in social media after their first appearance. We found that while almost 40% of the domains created 2006 were active five years on, only a little more than 3% of those created in 2015 remain active today.

The dynamics of online competition are becoming clearer and clearer. And the loss of diversity is concerning. Unlike the natural world, there are no sanctuaries; competition is part of both nature and business.

Our study has profound implications for business leaders, investors and governments everywhere. It shows the network effects of the web don’t just apply to online businesses. They have permeated the entire economy and are rewriting many previously accepted rules of economics.

For example, the idea that businesses can maintain a competitive advantage based on where they are physically located is increasingly tenuous. Meanwhile, there’s new opportunities for companies to set up shop from anywhere in the world and serve a global customer base that’s both mainstream and niche.

The best way to encourage diversity is to have more global online businesses focused on providing diverse services, by addressing consumers’ increasingly niche needs.

In Australia, we’re starting to see this through homegrown companies such as Canva, SafetyCulture and iWonder. Hopefully many more will appear in the decade ahead.

Full article published by the World Economic Forum

New research shows that the variety of online players is shrinking rapidly, although the overall size of the worldwide web continues to expand and functional and geographic opportunities are rising.

The Online Diversity Study published by Public Library of Science addresses an apparent paradox: the web is a source of continual innovation, and yet it appears increasingly dominated by a small number of dominant players.

This research tackles this paradox by using large-scale longitudinal data sets from social media to measure the distribution of attention across the whole online economy over more than a decade from 2006 until 2017. Here, we use outbound weblinks towards distinguishable web domains as a proxy for the market for online attention. As this data collection captures longitudinal trends relating to a universe of all potential websites and services, it serves as a valuable index of broader economic trends, dynamics, and patterns emerging online.

In this work, we provided evidence consistent with a link between increasing online attention on social media and the emergence (and growing) dominance of a small number of players.

The development of the web has been steady, and it came in functional waves, each of which has been predicated by the emergence of foundation platform technologies— such as secure encryption, enabling e-commerce; ubiquitous broadband, enabling the emergence of streaming video and mobility, enabling the emergence of many new functions including car sharing. This research outlines that while new functions, services, and business models continuously emerge online, the web dynamics are such that in many mature categories of online services, one or a small number of competitors dominate. Yet, as new web technologies continue to be developed, this enables more unexplored functional niches to emerge and for the cycle to repeat. Over time, this process leads to long-term declines in the overall competition, diversity, and decreasing survival rates for new entrants.

The world’s largest companies are now those that run global online platforms: Apple, Facebook, Google, and Amazon in the west and their counterparts Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent in China. There is a growing public interest in the nature and extent of dominance on the web and web giants’ influence on economics, popular culture, and even politics.

This paper extends understanding of the nature and scope of the web’s network effects on the evolution of businesses today. This work also opens the door to further research that uses digital footprints of organisations en masse as a basis for analysis of the behavioural economics and competitive dynamics of markets online. There is room here too for further work in simulation extending previous work done in synthetic market experimentation and prediction.

Innovative global products and services, such as TikTok, Klarna and SkyScanner, continue to emerge from a range of creators around the world.

What, no? Yes, Jobs have Personalities!

New Research Reveals the Hidden Personalities of Jobs

“When academic Paul McCarthy first started to map the personality traits of the top computer programmers and the top tennis players in the world based on the information they revealed on their Twitter feed, he thought he had made a mistake.”

“I nearly fell off my chair when I saw the results,” says McCarthy, adjunct professor at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. The computer and data scientist had used an AI tool to assess the Twitter accounts' language for insight into five key personality traits. “I thought I'd done something wrong, because I didn't think it could be right that all these people had such similar personalities,” he says.

McCarthy’s results found that the top 200 professional tennis players on Twitter showed remarkably similar personality traits. “They are largely very agreeable and very extroverted, very conscientious and they tend to score low on openness,” he says. While there were some exceptions, the computer programmers were broadly opposite.

Same profession, same digital footprint

Historically, careers advisers and researchers have broadly posited that certain personality types suit particular professions – that extroverts suit sales roles, for instance – but McCarthy says the scale of this recent research is markedly greater than earlier work in the field. "All the previous work in this area involves surveys. It involves as little as 50 people sometimes, and generally up to a few hundred people," he says. "Whereas this [Twitter study] is observed behaviour… at this scale you can see things you can't see elsewhere."

Researchers say that, if used ethically, the ‘vocation compass’ could help students narrow down career path choices by trawling their social media feeds. Researchers say that, if used ethically, the ‘vocation compass’ could help students narrow down career path choices by trawling their social media feeds.

For their study, published last month, the Australian researchers trawled the accounts of 128,000 Twitter users. The personality mapping tool, which requires around 100 pieces of self-written content about an individual’s life or thoughts to run its linguistic analysis, can also use content from things like emails or forum contributions. But the researchers chose to focus on Twitter to test the concept of matching personality to profession as it represented the largest source of content from a wide variety of individuals and professions.

The accounts – which self-identified the user’s profession – were measured in terms of their ‘big five’ personality traits: agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness (relating to a willingness to test new experiences or ideas, not interpersonal openness).

Whether the personality findings were absolutely spot on for each individual’s true self, Kern says, was not the subject of the test. What the research discovered, however, was a consistency: in their digital footprints, tennis players’ personalities looked remarkably similar to each other. Scientists looked remarkably similar to each other. The differences across the occupations were clear.

Full Story: BBC Worklife.

According to new research published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), understanding the hidden personality dimensions of different roles could be the key to matching a person and their ideal occupation.

The study’s findings point to the benefit of not only identifying the skills and experience needed in a particular industry, but also being aware of personality traits and values that characterise jobs – and how they align with your own.

The research team looked at over 128,000 Twitter users representing over 3,500 occupations to establish that different occupations tended to have very different personality profiles. For instance, software programmers and scientists tended to be more open to experience, whereas elite tennis players tended to be more conscientious and agreeable.

Remarkably, many similar jobs were grouped together — based solely on the personality characteristics of users in those roles. For example, one cluster included many different technology jobs such as software programmers, web developers, and computer scientists.

The research used a variety of advanced artificial intelligence, machine learning and data analytics approaches to create a data-driven Vocation Compass — a recommendation system that finds the career that is a good fit with our personality.

Co-author Paul X McCarthy, an Adjunct Professor at UNSW Sydney, said finding the perfect job was a lot like finding the perfect mate.

"At the moment we have an overly simplified view of careers as a race, with a very small number of visible, high-status jobs as prizes for the hardest-working, best connected and smartest competitors.

“What if instead – as our new vocation map shows – the truth was closer to dating, where there are in fact a number of roles ideally suited for everyone?

“By better understanding the personality dimensions of different jobs we can find more perfect matches."

Lead researcher Associate Professor Peggy Kern of the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Positive Psychology said that “it’s long been believed that different personalities align better with different jobs. For example, sales roles might better suit an extraverted individual, whereas a librarian role might better suit an introverted individual. But studies have been small-scale in nature. Never before has there been such large-scale evidence of the distinctive personality profiles that occur across occupations.”

Co-author Dr Marian-Andrei Rizoui of the University of Technology Sydney said they were able to “successfully recommend an occupation aligned to people’s personality traits with over 70% accuracy.”

“Even when the system was wrong it was not too far off, pointing to professions with very similar skill sets,” he said. “For instance, it might suggest a poet becomes a fictional writer, not a petrochemical engineer.”

With work taking up most of our waking hours, Professor Kern said many people wanted an occupation that “aligns with who they are as an individual.”

“We leave behind digital fingerprints online as we use different platforms,” said Professor Kern. “This creates the possibility for a modern approach to matching one’s personality and occupation with an excellent accuracy rate.”

The researchers noted that while the study used publicly available data from Twitter, the underlying vocation compass map could be used to match people using information about their personality traits from social media, online surveys or other platforms.

“Our analytic approach potentially provides an alternative for identifying occupations which might interest a person, as opposed to relying upon extensive self-report assessments,” said Dr Rizoui.

“We have created the first, detailed and evidence-based multidimensional universe of the personality of careers – like the map makers of the 19th century we can always improve and evolve this over time."

Tennis professionals like Maria Sharapova (pictured) share similar personality traits to her peers and rivals in tennis, but these traits are entirely different to those in other professions such as technology or science. johanlb/flickr, CC BY-SA

Conversational AI — the new wave of voice computing

Conversation is the key to the next wave of AI infrastructure investments.

In 2014, Andrew Ng predicted that by 2020 more than half of all web searches would be non-text and instead they would instead be image and voice-based. While voice has yet to overtake the keyboard in terms of search traffic we are seeing a new inflection point in the voice market the rise of Conversational AI. Moving beyond simply voice commands and by combining the latest in voice recognition and language parsing technology with text-based smarts of interactive chatbots that has been developing rapidly over the last few years, Conversational AI promises to be a rich new vein of technology innovation.

A range of new digital services are emerging as companies explore this new landscape of voice-first interactive applications that have the capacity to provide rich information as well as learning from interactions with users.

Read the full article published in Forbes here.

Why mediatech is the new fintech

The mediatech revolution is well underway. It’s in our lounge rooms, bedrooms and on our way to and from work. We’re tuning into Spotify, playing Fortnite and watching Netflix into the wee hours like there’s no tomorrow.

The term “mediatech” has been used for over a decade to label startups with a media and technology focus in the age of the web.

Today’s tech giants including Apple, Microsoft and Adobe all have their roots in media technology for the personal computer at the famous Xerox PARC - the revolutionary media research lab that reinvented the modern office in an age of the personal computer. Its legacy includes many of the things we take for granted in computers today such as the familiar windows, icons, mouse and pointer-driven graphical user interface, local networking and the faithful reproduction on printers of what you see on the screen.

So far however there has not yet been a mediatech “movement” in the way the 2015 fintech rush took off. Perhaps that is because many mediatech companies are still seen as music, games, photography, or advertising tech companies.

Many of the today’s largest players in financial services are fintechs from another era. Bloomberg, Vanguard and Computershare all began as pioneers at the intersection of technology and differing areas of financial services: revolutionising and later dominating the market data, index fund and share registry sectors respectively.

The real roller coaster ride for fintech began in January 2015 when leading US technology venture capital firm Andreesen Horowitz set up shop in London and invested in the UK-based global online cross-border foreign exchange startup Transferwise.

Andreesen Horowitz had previously backed Facebook, Skype and Twitter and so this triggered a global rush of excitement about the potential for further investments in this vein. In each year since, venture capitalists have made over 1,000 investments each year in fintech startups representing over US$12 billion per annum according to KMPG’s latest Pulse of Fintech Report.

Has mediatech’s day in the sun arrived?

Like finance, media and technology have enjoyed a long and productive history together. As early bedfellows, one of Hewlett Packard’s important foundation customers was the pioneering Walt Disney who was using HP’s oscilloscopes to create pioneering feature-length animated films like Fantasia — the first film with surround sound.

Next generation classified giants like Zillow, Seek and even dating services like eHarmony and Tinder are all mediatech companies at heart as they aggregate, organise and present photos, maps and data online. And popular collaborative services marketplaces like Kaggle, Deliveroo and Airbnb are also new forms of mediatech. Their principal functions are to create online platforms for third parties to meet, facilitate workflow and exchange services.

New media formats continue to be a source of innovation as dozens of high growth mediatech startups emerge around the world. They span everything from 3D printing, such as Formlabs in Cambridge, Massachusetts; to virtual reality, such as the enigmatic and secretive Magic Leap based in Florida. Outside the US, Oovvuu is another example, offering automated matching of videos, using artificial intelligence, with news stories and readers around the world.

Mediatech in everyday use

As we did with the Graphical User Interface desktop computing era, we are now seeing a new group of online media technology giants come of age who make our office life more productive. These include Campaign Monitor that makes beautifully illustrated email easy, Slack that makes it easy to share documents, photos and data across multiple devices, platforms and formats, and Buffer, that simplifies the scheduling of social media postings.

The potential for mediatech is enormous — today’s largest tech companies, each now worth over US$200 billion, got their start in mediatech - Apple with mobile music, Amazon by selling books online, Tencent with online gaming. And Facebook, Baidu and Google are all massive global marketplaces for advertising — using the power of the web to disrupt traditional media channels such as TV, newspapers and phone directories.

Softbank’s impressive founder Masayoshi Son began by bringing coin-operated arcade games like Space Invaders to the US.

One may ask is there an equivalent to Transferwise moment for mediatech?

In January 2018, Sequoia China led an investment in Sydney-based Canva that valued it at US$1 billion, crowning it the latest Unicorn. Canva is helping reinvent desktop design and has 10 million users in 190 countries. Given its predecessor Adobe’s valuation at US$106 billion it clearly has ample headroom for further expansion.

Are we are on the cusp of global #mediatech movement? That remains to be seen but the stage is set for investors, businesses and consumers alike.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Spotify is leading a whole new generation of mediatech companies that from augmented reality, 3D printing to massively multiplayer online games like fortnight.

There are now more than twice as many private companies worth more than US$1 billion (also known as unicorns) in mediatech today (116) than as in the more well-known financial technology (fintech) sector (52).

The total cumulative value of the Top 100 mediatech unicorns and recent ex-unicorns that have gone public such as Spotify, Dropbox and Snap! is now worth more than US$275 billion.

While Fintech and Mediatech have both been around for more than a decade, Mediatech is only now having its “Transferwise” aha moment where investors realise the massive global potential upside across many segments.

While Fintech has been around for over a decade, the party really only got started in London in 2015 as investors worldwide realised the massive global potential of big data, AI and over half the world now online for a range of financial services segments. The tipping point as Malcolm Gladwell would say was when leading US technology venture capital firm Andreesen Horowitz set up shop in London and invested in the UK-based global online cross-border foreign exchange startup Transferwise.

In 2018, online design software company Canva with investors crowning a next-generation global tech giant in the making and making the first Unicorn of the new year. Pictured - Chief Evangelist of Apple, Guy Kawasaki, is now working for mediatech unicorn Canva.

In June 2016 Finland’s Supercell (and maker of Clash of Clans) became Europe’s 1st decacorn (private tech co valued at over US$10bn) thanks to a majority investment from China’s Tencent.

Digital transformation has led to an expanding mediatech landscape that increasingly touches all industries. This map shows interconnecteness of global industries today in the mediatech world.

It’s the six-degrees of separation map of the emerging global mediatech industry landscape.

Starting with core media assets such as Broadcast Media, Newspapers, Marketing and Adverting and Design and now underwriting the growth of many other diverse sectors such as Computer Games, Luxury Goods, Furniture, Fine Art and Supermarkets.

The Rise of Unconventional Data

The Rise of Unconventional Data

One of the lesser understood aspects of what you can do with massive stockpiles of data is the ability to use data that would traditionally have been overlooked or in some cases even considered rubbish. This whole new category of data is known as "exhaust" data—data generated as a by-product of some other process.

One of the lesser understood aspects of what you can do with massive stockpiles of data is the ability to use data that would traditionally have been overlooked or in some cases even considered rubbish. This whole new category of data is known as "exhaust" data—data generated as a by-product of some other process.

Much financial market data is a result of two parties agreeing on a price for the sale of an asset. The record of the price of the sale at that instant becomes a form of exhaust data. Not that long ago, this kind of data wasn’t of much interest, except to economic historians and regulators.

A massive moment-by-moment archive of prices of shares and other securities sales prices is now key to many major banks and hedge funds as a "training ground" for their machine-learning algorithms. Their trading engines "learn" from that history and this learning now powers much of the world’s trading.

Traditional transactions such as house price sales history or share trading archives are one form of time-series data, but many other less conventional measures are being collected and traded too.

There are also other categories of unconventional data that are not time-series-based. For example, network data outlines relationships and other signals from social networks, geospatial data lends itself to mapping, and survey data concerns itself with people’s viewpoints. Time series or longitudinal data is, however, the most common form and the easiest to integrate with other time-series data.

![Location data from mobile phones means many companies now have people-movement data. [Photo: via The Conversation , Flickr user Andrew Hyde ] Consistent Longitudinal Unconventional Exhaust Data or CLUE data sets, as I’m calling them,](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53f944b2e4b0586eb80bfbd8/1475575823220-N8OZ1N7VEY23N4B5O5CF/3063110-inline-i-1-gold-mine.png)

Location data from mobile phones means many companies now have people-movement data. [Photo: via The Conversation, Flickr user Andrew Hyde]

Consistent Longitudinal Unconventional Exhaust Data or CLUE data sets, as I’m calling them, are many, varied and growing. They include:

foot traffic data

consumer spending data

satellite imaging data

biometrics

ecommerce parcel flow data

technology usage data

employee satisfaction data.

Visualisation of footfall data from the past nine years at Glasgow’s Tramway arts venue. Photo: via The Conversation, Flickr user Kyle Macquarrie

Say, for example, you are interested in the seasonal profitability of supermarkets over time. Foot traffic data may not be the cause of profitability, as more store visitors doesn’t necessarily correlate directly to profit or even sales. But it may be statistically related to volume of sales and so may be one useful clue, just as body temperature is a good clue or one signal to a person’s overall well-being. And when combined with massive amounts of other signals using data analytics techniques, this can provide valuable new insights.

RISE OF "QUANTAMENTAL" INVESTMENT FUNDS

Leading hedge fund BlackRock, for example, is using satellite images of Chinataken every five minutes to better understand industrial activity and to give it an independent reading on reported data.

Traditionally, there have been two main types of actors in the financial world—traders (including high-frequency traders), who look to make money from massive volumes on many small transactions, and investors, who look to make money from a smaller number of larger bets over a longer time. Investors tend to care more about the underlying assets involved. In the case of company stocks, that usually means trying to understand the underlying or fundamental value of the company and future prospects based on its sales, costs, assets, and liabilities and so on.

Aerial photography from drones and new low-cost satellites are one key new source of unconventional data.[Photo: Flickr user BxHxTxCx]

A new type of fund is emerging that combines the speed and computational power of computer-based quants with the fundamental analysis used by investors: Quantamental. These funds use advanced machine learning combined with a huge variety of conventional and unconventional data sources to predict the fundamental value of assets and mismatches in the market.

Some of these new style of funds, including Two Sigma in New York andWinton Capital in London, have been spectacularly successful. Winton was founded by David Harding, a physics graduate from Cambridge University in 1997. After less than two decades it ranks in the top 10 hedge funds worldwide with US$33 billion in assets under advice and more than 400 people—many with PhDs in physics, math, and computer science. Not far behind and with US$30 billion in assets, Two Sigma also glistens with top tech talent.

New ones are emerging too, including Taaffeite Capital Management, run by computational biology and University of Melbourne alumnus Professor Desmond Lun. Understanding the complex data dynamics of many areas of natural science, including biology and ecology, is turning out to be excellent training for understanding financial market dynamics.

WEIRD DATA FOR ALL

But it’s not only the world’s top hedge funds that can or are using alternative data. A number of startups are on a mission to democratize access to new sources. Michael Babineau, cofounder and CEO of Bay Area startup Second Measure, aims to offer a Bloomberg-terminal-like approach to consumer purchase data. This will transform massive amounts of inscrutable text in card statements into more structured data, thus making it accessible and useful to a wide business and investor audience.

Others companies, like Mattermark in San Francisco and CB Insights in New York, are intelligence services that provide fascinating and valuable data insights into company "signals." These can be indicators and potential predictors of success—especially in the high-stakes game of technology venture capital investment.

Akin to Adrian Holovaty's pioneering work a decade ago mapping crime and many other statistics in Chicago online, Microburbs in Sydney provides a granular array of detailed data points on residential locations around Australia. It allows potential residents and investors to compare schooling, restaurants, and many other amenities in very specific neighborhoods within suburbs.

We Feel, designed by CSIRO researcher Cecile Paris, is an extraordinary data project that explores whether social media—specifically Twitter—can provide an accurate, real-time signal of the world’s emotional state.

![We Feel is a research tool that creates "signals" data about the emotional mood of people around the world via their tweets. [Photo: via The Conversation, CSIRO ] WEIRD SMALL DATA HAS ITS BENEFITS AND ITS RISKS More than simply pop-economics,&nb](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53f944b2e4b0586eb80bfbd8/1475575827266-XVTR14TPN5L5JK5JKYOR/3063110-inline-i-3-gold-mine.png)

We Feel is a research tool that creates "signals" data about the emotional mood of people around the world via their tweets.[Photo: via The Conversation, CSIRO]

WEIRD SMALL DATA HAS ITS BENEFITS AND ITS RISKS

More than simply pop-economics, Freakonomics (2005) showed how unusual yet good-quality data sources can be valuable in creating insights. Assiduous record-keeping of the accounts of an honesty system cookie jar in an office place revealed that people stole most during certain holidays (perhaps due to increased financial and mental stress at these times); access to drug gangster bookkeeping accounts explained why many drug dealers live with their grandparents (they are too poor to move out); and massive public school records from Chicago showed parental attention to be a key factor in students' academic success.

Many of the examples in Freakonomics were based on small quirky data samples. However, as many academics are aware, studies with small samples can present several problems. There’s the question of sampling—whether it’s large enough to represent a robust sample and whether it’s a random selection of the population the study aims to understand.

Then there’s the problem of errors. While one could expect errors to be smaller with smaller sample sizes, a recent meta-study of academic psychology papers found half the papers tested showed significant data inconsistencies and errors. In a small number of cases this may be due to authors fudging the results, whereas others may be due to transcription or other simple mistakes.

WEIRD DATA IS GETTING EASIER TO FIND

More and more large-scale unconventional data collections are becoming readily available. There are three blast furnaces driving its proliferation:

the interaction furnace: our own growing interactions with the web and web services (e-commerce, web mail, social media) etc.

the transaction furnace: the increasingly online ledger of commerce.

the automation furnace: an explosion of web-connected sensors.

While large data collections can’t help with avoiding fabrication, they can sometimes help with sample size and representation issues. When combined with machine learning they can:

provide accurate insights from incomplete, noisy, and even partially erroneous data.

offer associations, patterns and connections—blindly with no a priori assumptions.

help eliminate bias—by invoking multiple perspectives.

Why startup investors love online marketplaces

A third generation of Online Marketplaces that combine workflow and networks are changing the underlying economics of many industries.

tiffany98101/flickr, CC BY

Read the full version of this article as originally published in The Conversation here.

Online marketplaces, also known as platform companies, are sprouting up everywhere and redefining business in every industry. “The Uber of ….” has become shorthand for tech startups looking to redefine the way everything is delivered, from legal services (Sydney-based LawPath) to Package deliveries (San Francisco-based Doorman), to Lottery services (Gibraltar-based Lottoland).

Paris-based Videdressing offers global aftermarket luxury branded fashion and Los Angeles-based DogVacay is an Airbnb-style online marketplace for dog vacations that has created a network of more than 20,000 pet sitters. It has raised more than US$45 million from investors.

Major online marketplaces are attracting the attention of leading technology investors. Last year Sydney-based Expert360, the global marketplace for consulting talent, attracted A$4 million; Artsy - the NY based global marketplace for artwork - closed US$25 million, and Shyp the San Franscisco based on-demand shipping services marketplace finalised another $US50 million in investment.

There are currently 5,723 early stage private online marketplace companies listed on AngelList the leading online marketplace for investors in early stage technology startups. The average valuation is US$4.5 million - so that is about US$25 billion worth of early stage startups in this area.

Why there’s no Pepsi® in cyberspace

In most industries today global competition thrives. And typically within each market in each industry there are leaders, challengers and often multiple niche players who can all eke out a good living. For example in the non-alcoholic beverage business, market leaders Coca-Cola and Pepsi have competed vigorously for more than a century. Despite this, both continue to be very profitable global enterprises, each with a market value of more than US$100 billion.

But in online global markets, the picture is quite different. For example, in the market for social media, one company, MySpace was the clear global leader in 2006 until its rival Facebook gained momentum and overtook it in less than two years. Once ahead Facebook went on to vanquish its rival and command almost complete control of the entire category, creating the first and only US$100 billion player in social media.

Read the full article published in The Conversation.

FAANG - The United Nations of Tech Giants

Global power is shifting from a society of nation states towards a society of global online companies. Many of the traditional roles of government such as the redistribution of wealth, the creation of public infrastructure and competition regulation are being tested by a growing constellation of planetary-sized online businesses such as Apple, Facebook, Alibaba, Tencent, Google and Amazon. Sometimes one grouping of the US companies in this club is referred to by investors as FAANG (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google) .

Even in that most rarefied role of the public sector – intelligence, government's potency and efficacy is now in question. In the latest 007 movie Spectre, James Bond's rival codenamed "C" says of their new impressive headquarters: "Her majesty's government wouldn't have the money to fund this – it's funded by a benefactor." And in the 2014 film Kingsman (which is intended to be a spy movie franchise) the central idea is one of a privately funded secret service, its founders having long given-up on the idea such an organisation could spring from and be run effectively in public hands.

In the spy game, government may not even have the best or most important secrets to guard anymore. Since 1960, industrial espionage involving theft of commercial technology and secrets has become the most written about aspect of spycraft in both fiction and non-fiction now receives five times the attention as military or political espionage.

Competition itself has to be understood differently in the online world because one enterprise can come to dominate a given sector very quickly. The merger of the number one and two US online real estate advertising companies Zillow and Trulia was approved in February after a six-month review by the United States competition regulator, the Federal Trade Commission, which concluded "the balance of evidence reviewed does not suggest that a hypothetical monopolist of real estate portals could profitably impose a price increase on agent advertising".

The decision was made in part because of a lot of the advertising budget for agents is still spent offline. And this is true – offline competition still does exist but this may miss an important point. Companies such as Airbnb face many rivals in traditional hotel business but very few, if any competitors in their space.

Competition policy redundant

And for many industries, competition policy is becoming increasingly redundant and difficult to enforce at a local or even national level. Consider the online transport giant Uber which offers to replace existing "regulated" city-wide taxi cab companies with one "user-led" global system based on the clever use of smartphone technology (effectively on the shoulders of another online giant, Apple) and global network economics.

This is effectively a new form of public infrastructure – thus replacing another role of government – which licences and regulates the service. And as a largely asset-free, networked marketplace its operators can undercut margins of municipal-scale operators, and give a better deal to drivers and customers in the process.

It's kind of like a global monopoly carve-up with the losers being the incumbent taxi-operators and taxi-plate investors who, not surprisingly are unhappy with this arrangement. Regulators are caught in the middle wanting to protect the interests of companies and drivers who have invested in (their) licences and at the same time listening to the interests of the public who want cheaper better transport options. And while in some jurisdictions, ride-sharing has been declared illegal; decisions of fragmented, individual regulators have little impact on the fortunes of these outsized global companies.

The massive scale of private sector online giants can be seen usurping another core function of government – wealth redistribution. The announcement by Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan that they'll give away 99 per cent of their astounding wealth, $US46 billion ($62 billion), subject to certain conditions, will form the largest philanthropic organisation on earth.

This new pledge amounts to the equivalent of about 10 years worth of the total foreign aid budget of countries such as Australia, Canada or Sweden and is in effect replacing another traditional and central role of government – that of taxation and wealth redistribution.

New kind of democracy

A new kind of global-industrial democracy is at work here as we consumers elect a series of companies as the global "ruling parties" over different aspects of the online economy Facebook (social media); Google (search); Amazon (retail) and Apple (mobile).

As with elected officials, their "campaign statements" principles count as they run for office: Googlers started off with the mantra "Don't do evil" and Apple offers close-to-magic products.

Unlike elected officials however, due to the economics of online gravity (new set of economic forces), once they reach critical mass they are effectively unassailable and have the potential to stay in office unchallenged for a very long time.

Each of these companies, and a growing number of others like them operate in more than 100 countries around the world but typically have their employment, R&D and head office concentrated in a handful of locations.

And while revenue for online companies is increasingly global, taxation paid by jurisdiction is not so evenly distributed. As Tax Commissioner Chris Jordan commented in April "This means the majority of profits made in Australia end up in Bermuda where no tax is paid."

The answer for government, to my mind, on many of these issues is to do as the online private companies have done – use the amazing power of the web to go global. In the decades ahead, foreign policy and multilateral collaboration is going to be increasingly important not simply on issues of national security and trade but in many areas formerly in the realm of domestic policy – such as taxation, privacy, competition policy.

Anyone, including government, wanting to be part of this new global game should make two notes: Stand on the shoulder of giants and be global in ambition.

Paul X McCarthy is the author of Online Gravity, published by Simon and Schuster. He owns shares in Zillow Group (NASDAQ:Z).

Originally published in the Australian Financial Review https://t.co/0JA1LPSKaL

While Kodak was an iconic and hugely successful global consumer products company - mentions in all printed books English language books never outnumbered the US Government — even during its heyday of the 1970s.

In less than a decade, Google on the other hand has overtaken the US Government in mentions in English language books in its brief but spectacular ascent to become one of the worlds most influential online giants.

Paul X. McCarthy says the answer for government on policy issues is to do use the power of the web to go global. Louie Douvis

Rocketing regions: the jobs of the future in gazelle headquarters

Do you know someone who has lost their job in the last few years working in IT, media, finance or retail? These industries and many others are already feeling the pinch of “online gravity” - a special set of economic forces and drivers that increasingly govern business in the age of the web.

Much has been made of the disappearance of jobs due to the digitisation, automation and networking of many traditional industries — most notably in traditional media. But careful global economic analysis has shown the internet has in fact added more jobs than it has destroyed.

According to McKinsey and Company the internet has created 2.6 new jobs for every 1 deleted. What’s becoming increasingly apparent however is the location and setting forwhere these new jobs appear is often not the same for those which were lost.

Online, business today is being influenced by a different set of economic forces than those that exist purely offline. I call these forces “online gravity” – not unlike the forces that led to the formation of our solar system. These forces favour the creation of planet-like superstructures with lots of white space in-between. In a former article (Why there’s no Pepsi® in cyberspace) I outlined this phenomena and here I examine how online gravity is reshaping the future of work.

Read the full article published at The Conversation here.

Big data platform technologies

While much focus and discussion of the so-called “Big Data revolution” has been on the data itself and the exciting new applications it is enabling — from Google’s self-driving cars through to CSIRO and University of Tasmania’s better information systems for oyster farmers — less focus has been on the underpinning technologies and the talent driving these technologies.

At the heart of the Big Data movement is a range of next generation database technologies that enable data to be amassed and analysed on a scale and speed hitherto unseen.

Global online services such as Google, Amazon and Facebook that serve billions of people around the world in real time have been made possible due to new technologies that divide tasks and files across banks of thousands of distributed computers.

Read the full version of this article as originally published in The Conversation here.